The Upcoming Economic Recession Could Be Far Worse Than the Great Recession of 2008

The United States. is heading toward another economic recession in 2017. If the U.S. enters a recession, it won’t be long before the rest of the world follows suit. There is an unusual level of uncertainty because the dark years of the Great Recession, or the 2008 recession, that started in 2008 have given way to real growth.

Global growth predictions stand at three percent. But in the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) countries, including the U.S. and Germany, gross domestic product (GDP) could hit just below two percent. In some once-leading economies like the U.K. and Italy, growth might reach one percent. In countries outside the OECD, GDP growth might be just above four percent.

Overall, after the last recession, these figures should have been much higher. Instead, the economic recovery is lukewarm at best. It’s not enough, then, to speak of an upcoming recession. The world never came out of the last recession. Even China has been forced to revise its GDP growth expectation downward.

China expects six to 6.5% growth in 2017. It could be as low as 5.5% in 2018. The next four years will feature several new terms that all begin with the word “Trump.” “Trumponomics” is one of the key terms that will help define the next era. What defines Trumponomics or, if you prefer, Donald Trump policies?

The Causes of Economic Recession in 2017

By the new U.S. president’s own description, infrastructure development will play a significant role in driving economic recovery. Infrastructure will serve as the base for Trump’s “America First” policy. But America First represents a much bigger disruption to the current globalist system. More than infrastructure, the America First policy brings back mercantilist policies.

This is not altogether bad. But it might be altogether impossible to achieve. Trump’s program is mercantilist because it wants to reduce America’s trade deficit by using its geopolitical clout to curb surplus from its main trading partners. Thus, Trump has essentially put China, Mexico and, evidently, the European Union (EU) on notice.

The problem is that the world has moved away from mercantilism over the past few decades. It has been moving away from that model, in fact, since the end of World War II. To promote greater security and lasting peace, states gradually lifted trade restrictions. In mercantilism, however, the state is solely dedicated to the promotion of its own national wealth.

Mercantilism wants to protect local products from external competition, while aggressively promoting exports and industrialization. It was a policy that found its most aggressive expression in the 16th–17th centuries. It was the result of capital influx in the form of precious metals mined in colonies to build up bullion rather than the multilateral free/freeish trade of the present.

The classic mercantilist state was Imperial Spain. The Spanish crown sought to accumulate a maximum of precious metals as a source of national wealth. The Trump administration would not reach that level of mercantilism. It would not pull out of international trade altogether, but it would tend to generate inflation and, therefore, higher interest rates.

Of course, it is the job of every state to protect its national interest. But the current “global” approach stressed that states could obtain the best compromise between growth and security through cooperation. Thus, looking out for the benefits of trade groups or trade agreements became the norm.

Apart from the EU, perhaps the most advanced example, there are important trading blocs such as ASEAN in Asia or Mercosur in Latin America. Agreements such as the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) were the latest such effort and one of the most ambitious where the United States was concerned.

Not surprisingly, one of President Trump’s first executive actions was to pull the United States out of the TPP. That was the first big mercantilist signal. The problem is that the rest of the world does not seem ready to go back to that model. That’s why there is no certainty that such a move improves the U.S. economic outlook 2017.

Indeed, because the U.S. seems to be the only economic power willing to exhume mercantilism from the tomb of dead economic theories, it will face resistance. In reality, the Trump administration cannot pull away from global trade. That would kill American business. Trump’s policies might favor local production and tax certain imports from China, but Trump may face challenges.

This Is Where Trump’s Plan Could Go Awry

Trump wants to cut imports but promote American exports. He has not shown any sign of discouraging American industrial output. On the contrary, he wants to increase it. But the idea that America can both defend its domestic market from imports while encouraging exports around the world doesn’t work. The rest of the world operates through trade blocs and agreements, and substitutes for American industrial products exist.

In addition, by pulling away from globalization, Trump would be doing a major disservice to the United States. Perhaps the point became lost during the presidential campaign, but no country, not even China, has gained as much from globalization as the United States. American technology has spread worldwide.

Global entrepreneurs have invested in the United States; they have listed their companies on the New York Stock Exchange (NYSE). The world invests in U.S. real estate and lives and breathes U.S. culture. Mercantilism may backfire, should it defy logic and socio-economic evolution, to become popular again.

Rather, while increasing the chances of a global economic recession, Trump’s “neo-mercantilism” puts the U.S. economy at greater risk. Yet, many rightly wonder, given all the risk of Trump’s policies, where are the signs of an economic recession?

It seems not a day goes by that Wall Street doesn’t hit a new record. The performance of the stock markets, and Wall Street in particular, speaks for itself. It was Dow 20,000 in December 2016. Two months later, the Dow seems headed for 21,000. But the stock market is detached from the real economy. Therefore, is the U.S. heading toward economic recession?

Don’t let the Dow Jones fool you. Trumponomics does have a special appeal for free markets. In theory, it promises fewer taxes, fewer regulations, more investment, and more spending on infrastructure. The effect of what Trump’s policies might unleash on the American economy should not be underestimated.

President Trump’s mercantilist and nationalist stance presents risks for the American and global economy. Simply put, the U.S. is still deeply intertwined in worldwide financial and economic affairs. A radical change of approach will therefore cause disruption. Perhaps, in time, some economies will recover, but the effects of the 2008 recession remain.

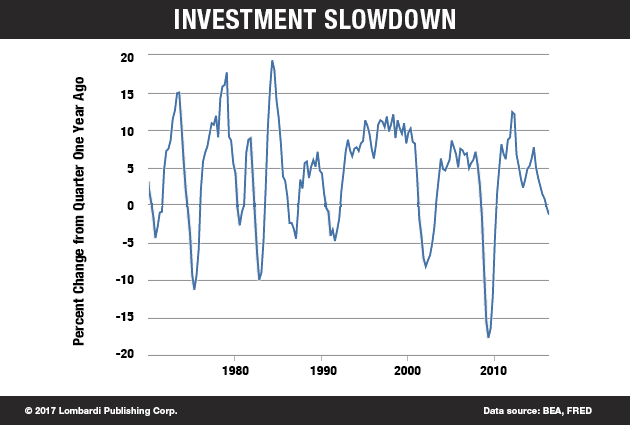

In other words, while there has been a financial recovery, the real economy remains in a recession state. The much-heralded recovery has not yet completed its course, if it ever began. One of the reasons is that investment has slowed down without recovering.

In this context, there is a pessimistic probability. Good political sense, reinforced by economic history, suggests that should Trump truly unleash a mercantilist and protectionist economic policy, he would trigger an equal escalation in the opposite direction. It’s not quantum physics, it’s basic mechanics: for every action, there is an equal and opposite reaction.

Yes, you recognized that as Newton’s Third Law of Motion. It doesn’t just apply to physics. Trump’s economic aggression against China and Germany, and also Mexico and Japan, could backfire. These are the biggest exporters of the planet. They have considerable external surpluses.

The United States cannot afford the luxury of protectionism. Not in this world and not now. Trump has claimed that China’s trade surplus is the result of a deliberate policy of devaluing its currency, the yuan. Nothing could be further from the facts. China has tried its hardest to stem capital flight. That’s what has caused the yuan to fall.

Trump has accused Germany of manipulating the euro to its sole benefit at the expense of its EU partners. He may be more correct on Germany than on China, given what many Europeans say, but such logic also has flaws. Trump’s mercantilism would promptly crash with harsh reality.

The United States is much more involved in world trade than in the golden age of American supremacy, in the immediate aftermath of the world war. Trade’s share of GDP has more than tripled since 1950, from four percent then to 13% in 2016. More significantly, the peak in manufacturing jobs in the U.S. has been declining since the 1950s.

When Trump speaks of bringing back manufacturing jobs, he seems to neglect some basic facts. In the 1950s, manufacturing jobs accounted for about 30% of the total. By 2016, the share had dropped to eight percent. (Source: “Tough talk on trade will not bring jobs back,” The News, February 6, 2017.)

Protectionism Can’t Work in 2017

When you add the protectionism that Trump’s mercantilist policies will generate, it seems impossible to achieve that kind of leap into nostalgia. Trump’s policies would surely achieve one thing: a drop in world trade—which is already sluggish—and an economic recession worldwide. All the while, the higher Fed interest rates would exacerbate that risk, while boosting the value of the dollar, making U.S. goods less competitive.

As a result, the recent market euphoria and the “Trump effect” are more the products of the American economic recovery that began a year ago. The stock markets are feeding themselves, surprised that general consumer appetite has not dwindled. But, this is short-term.

Trump’s protectionist policies would enforce duties of up to 35% on foreign goods. This would certainly achieve the goal of making imported products more expensive. But, it would drastically reduce consumers’ purchasing power. It would also cut the competitiveness of American companies, which depend on the imported components.

Meanwhile, China and Europe could also increase tariffs as a reaction. This would result in an all-out trade war. The whole global economy would suffer severely from the resulting isolationism. The first effect would be the loss of millions of jobs worldwide—and the United States would not be spared. The result is depression, not even recession: total economic collapse.

The markets are not interpreting Trump’s policies as much as what the president has said about his policies. There is a difference. Trump’s policies do not represent anything new, much less revolutionary. They are a mild version of basic mercantilism. Under Trump, America expects to grow by promoting as much economic activity as possible within its own borders.

Trump has already shown he plans to protect American industry through tariff barriers. Trump plans to increase spending on the military, which is good for defense sector stocks. But a bigger military might be needed to enforce the kind of political power relations to support exports. Of course, a bigger military and ever more expensive equipment require taxes.

Trump has not indicated where the money to fuel this kind of economy would come from. He wants to reduce taxes. In any economic outlook 2017, Trump has generated risks linked to protectionism, populism, anti-Europeanism, anti-China sentiments, and immigration.

As for the latter, the economic success of the U.S. is strongly dependent on the knowledge and experience of immigrants. Innovation would suffer. Many experts, scientists, and academics, would tend to avoid visiting the U.S. because of doubt about their status. Let’s not forget that the leaders of the U.S. atomic program or the space program were immigrants.

Trump has overshadowed the more pressing issues of an aging population and the technological/digital revolution, which will make much of current work redundant. Robots are ready to replace many human functions. These factors, left unheeded, have dangerously become less pressing, even if they are much more destabilizing.

Trump might try to mitigate the effects of his protectionism. He will likely dissuade the U.S. Federal Reserve Chair Janet Yellen from raising U.S. interest rates to keep the dollar competitive. If Yellen doesn’t comply, Trump would find an old trick from his The Apprentice handbook: “You’re fired, Janet!”

To protect yourself against the risk of the almost inevitable recession on the horizon, there are solutions. Learn what you can now, while others revel in the fragile safety of the markets.