The Fed Wants to Increase Interest Rates in March 2017

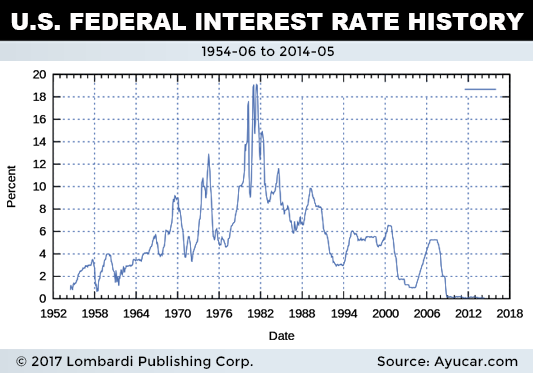

Janet Yellen, Chair of the Federal Reserve (that is, the U.S. central bank), hinted that a Fed rate hike is coming. Indeed, the Fed wants to increase interest rates in March 2017. In simple terms, what effects on the markets and the economy could a rate hike imply?

A March interest rate hike could have a major effect on the markets. But, it’s not clear what effect. Thus, Janet Yellen will be taking a major risk with the U.S. economy. The risk is magnified by Trump policies. Since Donald Trump has taken office, the markets have soared on unrealized promises of all-around corporate and personal tax reductions and infrastructure spending.

Janet Yellen has succumbed to the pressure. Many economists think that the soft monetary policy of low interest rates is no longer the sharpest tool in the financial shed. Low interest rates appear to have come to the end of the line. Yet, as soon as the media alerts that “the Fed hikes interest rates,” it triggers panic in the financial markets.

A central bank raises rates to increase the cost of money. That is, the cost that private banks pay to borrow liquidity from the central bank or the Federal Reserve—in the U.S. case. That nominal interest rate affects those that individual banks apply to consumers. The interest rate tool is used as an accelerator pedal to slow or speed up the economy.

Many believe, Janet Yellen included, that Trump policies will boost inflation. An excessive rise in inflation, even stagflation is possible in 2017 or 2018. Inflation erodes the value of a currency and therefore reduces people’s ability to buy things. Beyond a certain point, the public has little reason to welcome the current U.S. interest rate predictions.

The Fed Is Taking a Major Risk by Raising Rates

International convention dictates that an acceptable and healthy level of inflation for economic growth should be close to two percent. If inflation is lower, it means that something is either very right or—as in the present case—very wrong. When inflation is too high (four to five percent) it could mean that the economy is overheating.

Like an engine, higher inflation suggests that the economy is growing too fast for its potential. That happens when an excess of loans becomes the main growth driver. That’s why the Fed intervenes. It raises rates and pushes private banks to draw out less liquidity. Thus, private banks have less money to lend to businesses and households.

After the 2008 financial crisis, the developed economies stopped growing. There was deflation. Conversely, despite the low interest rates, banks made it much harder for private individuals and businesses to borrow. That has warped the economy. That’s why the coming regime of higher rates presents such risks. Nobody knows what could happen.

The effects of interest rate hike woes have been especially sharp in Europe. When the European Central Bank (the equivalent of the Fed for Europe) said it would not extend quantitative easing (QE), the stock markets took flight last September. Rumors that the Fed and Bank of Japan would also lift rates triggered a wave of volatility.

That’s why the Fed, which expects to raise rates to close to 2.5% by 2018, has taken so long before considering this step. And if the Fed raises rates, the troubles increase. That’s why the Fed has taken its time. But, if inflation and the U.S. economic outlook 2017 unveil as expected, the Fed will feel compelled to act.

If rates go up as expected, it has no choice to act. The rate hike program for 2017, given that near zero interest has softened financial instincts, will fundamentally affect the risk map. Vulnerability to black swan events and volatility will change in a matter of months. It’s been so long since interest rates have been in zero-percent territory that nobody knows what could happen.

Thus, after virtually three months of Dow Jones Index record highs, federal interest rates rising will bring volatility back. It will be the kind of volatility that only the Federal Reserve can provide. Janet Yellen will deliver the rate hike in her customary and just shy of scintillating tone. But she will no doubt infuse some unpredictability in the markets.

In fact, as the Fed hikes interest rates, it could end up separating the hype stocks from the reality stocks. It could be a proverbial pileup. Indeed, despite the market exuberance there is still no evidence that Trump policies will work. The markets have been on a bull run to rival Pamplona for weeks, but nobody know if the bull has taken steroids.

If the next earnings season doesn’t beat expectations, the March interest rate hike will raise a stark contrast with Wall Street. That contrast could weigh significantly on stock market performance in the future. Especially if the Fed should lift rates further during the course of the year. A U.S. stock market crash is possible, if not probable.

The Fed hike will show whether the markets have simply been rallying on buybacks. Until a few months ago, the big fuel for the Dow Index has been buybacks. (Source: “It’s past midnight for the US share buyback bonanza,” The Financial Times, September 9, 2016.) Goldman Sachs Group Inc (NYSE:GS) estimated that between 2012 and 2015 companies spent $1.7 trillion just buying back their own shares.

That has been one of the true factors inflating the American Stock Exchange. The problem is that as buybacks gradually drop, the Wall Street records will fade. Thus, if corporate profits won’t exceed expectations, the entire house of cards will come tumbling down. The federal interest rate hike will cut the air from the present bull market.

Do the Employment Numbers Really Mean More People Are Working?

Meanwhile, the news coming from the U.S. labor market for February, Donald Trump’s first full month in office. The United States created 235,000 jobs in February. That is better than expected, with the unemployment rate dropping to 4.7% from 4.8%. That is in line with expectations.

Hourly wages also increased along as forecast by analysts. But there is a fact that should have raised investors’ concerns. It could affect market performance in the next few months. There are fewer people who need a job—or are looking for one—now, the lowest numbers since April 2016.

There are two ways to interpret that. One is to take the data at face value: there are fewer people who want a job. The second way is to look deeper and consider the possibility that many people are either underemployed—working in positions paying less than what they’ve become accustomed to—or simply too discouraged to look.

Unfortunately, the jobs data makes a stronger case for the Federal Reserve to raise rates. The job numbers will be seen as a sign of economic health. The fact that the Trump policies have yet to materialize has no bearing. Indeed, nobody knows what the effects of the Trump policies might be. In February, nothing has changed from the last months of the Obama administration.

But Trump has promised to make radical changes. So, the rate hike will come as a response to policies established by the previous president. They might not suit the outcome of Trump’s plans. There are no guarantees that jobs in the United States will continue increasing at the current rate.

The employment numbers have merely served as an excuse to prolong the one thing that’s truly overheated now: the performance of the financial markets. But, most analysts make the mistake of confusing the fact that what’s good for Wall Street may not be as good for Main Street or the real economy.

If the interest rate hike makes life more difficult for families and businesses (the real economy), it could lead to another financial collapse. Eventually, the markets get the message from the Street. Some might say that higher interest rates will make it easier to save. But, who is earning enough to save anything of substance today in the first place?

Meanwhile, so long as job growth remains within expectations, the Fed will proceed with lifting rates in 2017. As many as three hikes can be expected if job numbers stay on par. Then there is the problem that the U.S. economy, no matter Trump’s efforts to pull out, remains an integral piece of the global economic puzzle.

The Federal Reserve Worries About Emerging Economies

Many have suggested that U.S. inflation could finally move above the two-percent threshold in 2017. That’s why the Federal Reserve is trying to normalize monetary policy, raising the cost of borrowing between to two percent or higher and up from the current 0.5%. But the Federal Reserve is struggling to raise interest rates, because the effects of monetary tightening will affect other countries.

The Fed worries about a domino effect following the rise of Federal interest rates in the US on emerging economies. One of these is China. One of the characteristics of emerging countries is to have on average higher interest rates than developed ones. They attract foreign capital by offering higher returns.

In recent years, especially after Fed rates went to near zero, many companies from emerging countries have issued bonds in U.S. Dollars. They did this to exploit such low rates and the low value of the Dollar. The weaker dollar has allowed emerging countries to convert their debt into dollars. Thus they have taken advantage of lower interest than if they had saved in their local currency.

If—or rather, when—the Fed hikes rates, the dollar will appreciate, as will the interest on their debts, turning advantages to obstacles. As interest rates in the U.S. rise, it will become more expensive to borrow dollars. A stronger dollar leads foreign companies or governments to use up more local currency to repay the debt, if there are no dollar deposits.

It means that higher borrowing costs for businesses and governments, together with a stronger dollar, will increase the risk of collapse for the global economy, which has not fully recovered from the shock of 2008.