Inflation vs. Deflation Is the Biggest Risk to Consumers

Views about the battle of inflation vs. deflation in 2017 and beyond are not unanimous. Both forces are facing strong headwinds that could tip the balance toward their spheres of influence. We can see the battle take place with the erratic movement of 10-year Treasury note prices following the election of Donald Trump as president.

With the U.S. Federal Reserve raising interest rates, more alternation is likely. But one thing remains certain: the temperate pace of Consumer Price Index (CPI) increases of two percent is likely to give way sometime in 2017, or soon thereafter.

Inflation vs. deflation which is worse? Let’s try to make sense of it all.

For historical context, the current U.S. inflation rate is hovering at 2.7%, versus an average inflation rate of 3.2% in the long term. The previous decades between 1990–1999 and 2000–2009 experienced 3.0% and 2.6% annual inflation, respectively. This decade, it’s even lower: around 2.2%. If the Federal Open Market Committee members are to be judged on their ability to keep inflation near their two-percent target rate, they’ve done an exemplary job.

But times of inflation stability could be changing, due to various economic and political realities embedded in the current landscape. The CPI has been creeping up from the zero-bound level since mid-2015, and the election of President Donald Trump brought uncertainty to major inflation influences like free trade, deficit spending, and employment on-shoring. There’s a palpable sense of animal spirits lifting expectations of growth, dragging inflation expectations along with it.

Some notable market kingpins seem to think so.

In his yearly letter for 2017 to investors, hedge fund manager and Hayman Capital Management, L.P. founder Kyle Bass is making huge bets that inflation will take hold. According to Bass, “Global markets are at the beginning of a tectonic shift from deflationary expectations to reflationary expectations,” characterized by tepid growth and severe imbalances in established economic systems and currency markets. (Source: “Kyle Bass: ‘Global markets are at the beginning of a tectonic shift’,” Yahoo! Finance, January 4, 2017.)

Bass’s fund has increased 436.75% in total since its inception in 2006, for a compounded annualized return rate of 16.70%. Such a performance is not attained by being wrong very often.

Investment banking giant Goldman Sachs Group Inc (NYSE:GS) also believes that inflation will rise. In fact, the reflation trade is #5 on its list of “Top Trade Recommendations for 2017.” Goldman Sachs believes that headline CPI could rise in 2017, owing to “base effects from energy components,” and this could “influence inflation expectations positively.” They also cite the declining influence of austerity programs and central bank inflation target overshoots as reasons why inflation should pick up. (Source: “Goldman Reveals Its Top Trade Recommendations For 2017,” Zero Hedge, November 17, 2016.)

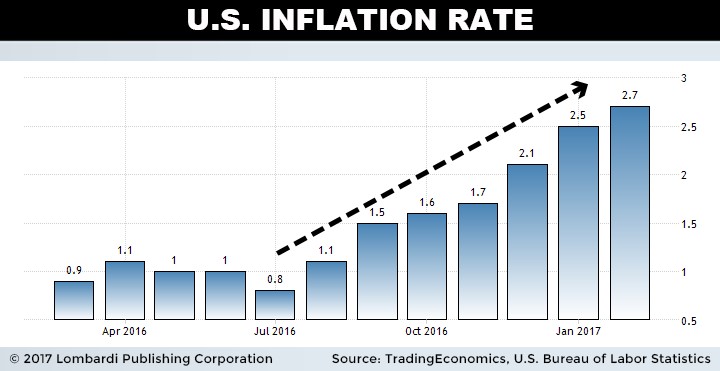

These views are part of a general consensus that inflation is on the upswing for 2017. So far, the numbers have borne this out. It’s still early in the year, but the U.S. inflation rate has risen from 2.1% in December 2016 to 2.7% in February 2017, although the 10-year Treasury Note yields are only down slightly.

What Is the Difference Between Inflation and Deflation?

At its core, “inflation vs. deflation” is a very simple concept. Inflation is simply too many dollars competing for too few goods or credit, driving these costs higher. Inflation is not simply a monetary phenomenon achieved by an overactive printing press, as understood in the classical sense. It can also be achieved when input costs rise or when wages run too hot. Essentially anything that causes a supply/demand distortion between money and goods has the potential to cause inflation.

By contrast, deflation is the exact opposite. The “value” of money increases when there are too many goods chasing too few dollars. Just like inflation, there are several factors which can cause it: industrial overcapacity, slack consumer demand, a widescale crash of credit applications. Anything that leads to an oversupply of a particular good or service has the potential to cause deflation.

The U.S. housing bubble of 2008 was a classic example of how massive oversupply of houses on the market (mainly through default), combined with crashing demand for credit, leads to collapsing home prices in the U.S. and weak economic growth. Deflation teetered on the brink n 2008, and again at certain points in 2015, but ultimately never materialized.

Annual U.S. Inflation Rates (Since 2000)

| Annual Inflation

(December vs. December) |

Inflation Rate |

| 2016 | 2.07 % |

| 2015 | 0.73 % |

| 2014 | 0.76 % |

| 2013 | 1.50 % |

| 2012 | 1.74 % |

| 2011 | 2.96 % |

| 2010 | 1.50 % |

| 2009 | 2.72 % |

| 2008 | 0.09 % |

| 2007 | 4.08 % |

| 2006 | 2.54 % |

| 2005 | 3.42 % |

| 2004 | 3.26 % |

| 2003 | 1.88 % |

| 2002 | 2.38 % |

| 2001 | 1.55 % |

| 2000 | 3.39 % |

(Source: “Historic inflation United States – CPI inflation,” inflation.eu, last accessed March 23, 2017.)

Causes and Effects of Inflation

Let’s say you borrowed money from a credit union with a five-year term. If inflation increased during this term, the value of the payments made to the credit union in current dollars is less than the purchasing power it afforded when the loan was initiated. In this case, higher inflation would be good for the borrower and bad for the lender. A higher level of inflation would knock out some of the sting of the massive consumer debt held in mortgages, consumer durables, and credit cards throughout the nation. It’s doubly true if real incomes rise in proportion to the measured inflation rate.

However, a rising inflation rate carries major drawbacks. Purchasing power is curtailed as prices for consumer goods become more expensive. Many find their standard of living eroded by a soaring cost of living, in which corresponding wages often don’t keep pace. The Federal Reserve generally raises interest rates in lockstep with rising inflation, as a tool to curb consumer demand for goods and credit. This raises mortgage rates, and loans become more expensive. For average Americans not carrying debt, most consider the effects of high inflation quite insidious.

Causes and Effects of Deflation

Deflation, on the other hand, is understood to be a general decrease in the cost of goods and services. Most people consider paying less money for things as a net positive. With all things being equal, and excluding debtor payment obligations, it is. Interest rates will generally rest at rock-bottom levels, allowing for lower financing costs. The price of goods declines, leading to greater ease of consumption.This equals greater net purchasing power. Who wouldn’t want that?

While lower prices are not negative in the short term, they can be if the lower prices persist. Decreasing price levels mean lower corporate profits, which in turn leads to higher unemployment and decreased economic output. Manufacturing productivity then declines. Consumers hold off on purchasing goods they believe will be cheaper a few short months later, further dampening economic growth. It’s not an easy task breaking a deflationary spiral. Look no further than the Great Depression—or present-day Japan—to witness the negative effects that long-term deflation can bestow on an economy.

Inflation vs. Deflation in the Future

The big question for U.S. consumers is where “inflation vs. deflation” is headed in 2017 and beyond. Lower-to-middle-class consumers are most affected by rising inflation rates, since this class has the least amount of discretionary income to buffer against its effects. People on fixed incomes are also on the front lines. Many people sense that their standard of living is slowly decreasing over time, yet can’t quite put their finger on the cause. Likely, it’s due to costs, both stealth and overt, increasing faster than their paychecks over time.

For this reason, there’s a big spotlight on the Trump administration’s economic policies in 2017. They will hold the key on whether inflation kicks into overdrive, or stays somewhat sanguine. Unfortunately, there are some worrying trends on the horizon.

There’s a good chance that input price inflation may be making a comeback if Trump’s rhetoric of import tariffs plays out. Trump has threatened punitive tariffs of up to 35% on internationally originated imports, and Trump will have a tough time walking that back. Reducing massive trade deficits was a core campaign promise; if Trump seizes ground on this issue, the basis of his “America First” platform vanishes into thin air. The movement of jobs and manufacturing operations back to America depends on evening out balances of trade.

But, by doing so, the risk of retaliatory trade measures, and ultimately, input price inflation lurks in the background.

For example, China has a track record of retaliating in trade disputes. In one example, China hit back against the United States by taxing U.S. chicken parts in 2009 after the Barack Obama administration slapped tariffs on Chinese tire imports. China’s mouthpiece newspaper, Global Times, has stated that “China will take a tit-for-tat approach” if punitive tariffs of up to 45% on Chinese imports are enforced. (Source: “China for ‘tit-for-tat’ if Donald Trump wages trade war: Chinese media,” Deccan Chronicle, November 14, 2016.)

Now, imagine how much the goods at your local Home Depot Inc (NYSE:HD) or Best Buy Co Inc (NYSE:BBY) would cost if Chinese imports were slapped with a 35% tariff. Corporate America wouldn’t be eating the balance of costs; it would be the consumer picking up the tab.

This could also happen in reverse: China could retaliate by slapping similar cost increases on essential commodities like rare earths, integrated circuits, or iron. This would make finished goods made in America more expensive, with consumers paying the bill.

There’s also Trump’s plan to slash income and corporate tax rates to rock-bottom levels, along with a profound deficit spending program. The former would cause more discretionary income to be floating in the real economy, while the latter would pile on already-stratospheric levels of debt.

The resulting deficit-fueled crack-up boom would cause upward pressure on wages, with the U.S. labor force already at near-full employment of five percent. The rebuilding of the manufacturing base in a tight labor environment is no small task.

In the end, although competing factors are currently keeping the inflation rate at manageable levels, the inflationary forces appear to be gathering steam. The U.S. forecast for the next five years should concern most Americans who care about maintaining their standards of living. Unfortunately, we think the subtle effects of inflation will gradually unfold to the detriment of wealth preservation everywhere.

Let’s hope the inflationary burner turns off, giving the boiling frog some relief.