The Stagflation Risk in 2017 Is at the Highest Point Since ‘70s

Inflation could rise beyond control to the point that the U.S. economy faces a stagflation risk in 2017. The signs are ominous; Janet Yellen will most likely raise interest rates three times over the course of the year. But, too many confuse a bullish stock market performance with the strength of the real economy.

So many questions remain about how the polls could have misjudged the extent of Hillary Clinton’s unpopularity. The media’s financial collapse scenario has not materialized. Financier George Soros has lost a billion, having bet short on the markets, when they went way long. Still, Trump’s election remains a paradox and after years of deflation, stagflation might replace it.

There’s no doubt that 2017 has started well. Many would be justified in wondering about the acumen of anyone who would suggest caution in the markets. The financial climate appears to be ideal. But don’t be fooled by favorable appearances. The markets seem to serve one year of decent economic growth and inflation.

Closer inspection suggests nobody should feel smug enough to drop their guard just yet. The risk of inflation and stagflation are upon us. What can go wrong in 2017, enough to dramatically change the investment scenario?

What Is Stagflation?

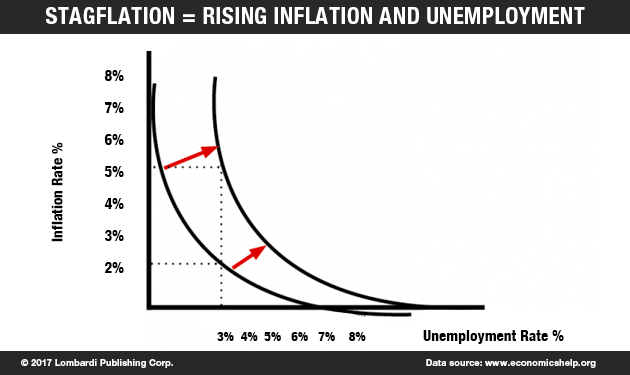

Stagflation is a term that British politician Iain Macleod coined in 1965. It derives from his combining the words stagnation and inflation. It refers to an economic situation where inflation is high, economic growth is slow, and unemployment rampant. What are the causes of stagflation?

To make this phenomenon clearer, the risk of stagflation in the eurozone is low. Such prospects are sill far away, because inflation, in the most optimistic of estimates, is at 0.4%. Indeed, many EU economies have been flirting with deflation. Low inflation is not necessarily a sign of economic health.

After a recession—or depression—as deep as the one that began in 2007, rising inflation is a sign of recovery. Inflation, in that case, can be considered as important an indicator of economic growth as higher GDP and wages. But, if employment and wages do not rise in step, the rising inflation might point to more problems than benefits.

Is the U.S. Entering into a Stagflation?

That’s when the risk of stagflation manifests itself. That’s why there is a risk of stagflation in the United States. Where there are expectations of rising inflation, in combination with slow economic growth, the discussion turns to stagflation. The causes of stagflation as far as the United States are ominously present.

One of the key factors, as well as the self-perpetuating effects of stagflation, is unemployment. The unemployment rate forecast in 2017 is not optimistic. Investors’ expectations are clear. As the market has amply demonstrated after Trump’s election, more tax incentives and deregulation are favorable factors to reflating the U.S. economy.

But, the financial sector is not the whole economy. In an ideal world, the financial sector would only serve as a facilitator or a tool of the real productive economy. So, what is good for finance should not be confused with what is good for ordinary hard-working folks. Certainly, inflation is widely predicted in 2017. That means that there are rising interest rate predictions for 2017.

The rising interest rates are intended to prevent the economy from “overheating.” But, interest rates have not increased in years. A single hike of the key interest rate could act as a shock to the system. However, Janet Yellen and the Federal Reserve seem ready to raise rates as many as three times in 2017. That could be premature.

Apart from other factors, rising national debt could stall the U.S. economy before it even has a chance to climb. The Fed’s interest rate hike could serve as the trigger mechanism for an economic collapse. Healthy inflation hovers around the two-percent range. But the interest rate hike adds an unquantifiable risk against the U.S. economic outlook for 2017.

Donald Trump policies are expected to boost inflation. But, even a small interest rate hike now could prevent those same policies from succeeding. As the chart below shows, U.S. inflation has been higher than the Fed’s ideal rate of two percent. The rate has hovered closer to the six-percent mark on average:

U.S. Inflation and Unemployment Rates by Year Since 2007-2008 Crisis

| Year | Avg. U.S. Inflation Rate by Year | U.S. Unemployment |

| 2007 | 2.8% | 4.6% |

| 2008 | 3.8% | 5.8% |

| 2009 | -0.4% | 9.3% |

| 2010 | 1.6% | 9.6% |

| 2011 | 3.2% | 8.9% |

| 2012 | 2.1% | 8.1% |

| 2013 | 1.5% | 7.4% |

| 2014 | 1.6% | 6.2% |

| 2015 | 0.1% | 5.3% |

| 2016 | 1.3% | 4.9% |

| 2017 | ? | ? |

(Source: “Historical Inflation Rates: 1914-2017,” U.S. Inflation Calculator, last accessed March 9, 2017.; “Unemployment rate in the United States from 1990 to 2016,” Statista, last accessed March 9, 2017.)

Low interest rates have helped the economy survive since the recession of 2008. In 2007, before the Lehman Brothers Holdings, Inc. crack, the economy was, at least statistically speaking, close to ideal. Average inflation was 2.8% and unemployment was 4.6%. But, as the economy entered recession in 2008, it took at least eight years before unemployment returned below five percent.

The Stagflation Scenario

But, while Donald Trump policies may produce the kind of growth he boasted before the election, there’s no certainty of this. The financial markets have reacted with a dangerous euphoria that could be setting themselves up for a major financial collapse in 2017. Thus, normalizing long-term rates now would be premature.

Increasing interest rates is the instrument of choice for central banks to fight inflation. But, as the chart above shows, inflation has just started to recover. In 2009, it was even negative: there was deflation, meaning the economy didn’t just stop growing—it was shrinking. Inflation recovery has been spotty and slow since then.

After trifling with deflation again in 2015, it just started to grow again in 2016. Since the 2008 financial crisis, the Fed and central banks of the world’s top economies—the U.S. is still the biggest—has been to lead the economy out of recession, boost growth, and reach the inflation target. The low interest rates may have helped stave off disaster, but they have had little impact on growth.

Indeed, the same central banks have had to adopt extraordinary monetary policy measures called quantitative easing (QE) to help give these economies a boost. Despite the optimism, much could go wrong in 2017. The first and rather obvious problem is that increasing inflation expectations could be wrong. Just as the pundits and pollsters who made such miscalculations with Hillary Clinton’s chances at winning the election, they could go too far.

Excessive—and flawed—inflation expectations are about as bad a basis to guide monetary policy and interest rates as there can be. Especially, when Donald Trump’s policies for success, and the market rally, rest on an overly optimistic tax reform. This is one of the core measures hailed by the Republicans in Congress.

But, there’s a basic arithmetic problem that doesn’t balance the books. Trump wants to spend over $130.0 billion on infrastructure. This might grow to a trillion dollars through the engagement of PPP (public-private partnership) mechanisms. Not much has been mentioned about wages rising. If wages do not rise in step with inflation, it makes no sense to speak of robust growth in the U.S.

If inflation rises and job numbers and wages don’t increase in turn, stagflation could be one of the effects.

The middle classes, once the engine of growth in the United States and other mature economies, have suffered for almost two decades. The elites have gotten away with obscuring this problem because the middle classes of developing economies have grown tremendously in that same period.

As a side note, should inflation rise as hoped, the risk that it could turn into stagflation suggests investors hedge their bets. They should diversify asset classes (gold comes to mind) as much as possible, even considering diversification in different territories. That would allow investors to benefit from potential growth in other markets.

Janet Yellen does her job, likely overseeing three rate hikes in 2017 in expectations of inflation. Trump has promised growth, but while doing so, he also intends to protect the American economy from external competition. Measures to protect the U.S. domestic market are not new. But the sudden shift from Obama’s globalization economics to Trump’s inward-looking approach conceals many shocks.

Trump’s protectionism has caused relations between China and the U.S. to soar. This will have repercussions on the economic stability: Consider that among the rich countries, more than 25% of employment is dependent on foreign demand, so if you decrease trade, it’s easy to see that economic growth would suffer.

Normally, inflation puts upward pressure on interest rates. Stagflation would only exacerbate that problem, slowing growth further. But, it’s difficult to see inflation being generated by an economy that is benefiting from increased demand. Furthermore, the reciprocating cycle of higher tariffs would make consumer goods and raw materials more expensive.

Service would suffer as well. The result will be the perfect stagflation storm: a combination of inflation and a slowing economy. Households will have less money to spend, furthering economic slowdown with all its negative effects.

Essentially, Trump could end up dragging the United States away from the global trade system. Protectionism is reciprocal. Higher tariffs on foreign goods automatically provoke higher tariffs on American goods. Protectionism limits the boundaries for economic growth. But, as the Fed acts to shield the economy from inflation, it increases the risk of events triggering stagflation.

A black swan even could ignite stagflation, putting pressure on the possibility that the “normalization” of U.S. monetary policy might move too fast for the overall economy. Moreover, if the Fed reads the economy wrong, Yellen’s resignation is just one effect. The financial markets could react negatively; they could collapse.