Stock Market Crash Signals Vulnerability to Missed Expectations

The November 9 market crash on the NASDAQ didn’t escape most traders. It was a rapid move lower, propelled by a light miss in the initial jobless claim numbers (239,000 versus the expected 231,000) and an overstretched market starved of reasons to keep moving higher. But why did liquidity dry up on such relatively benign data? Investors staking large positions here should be asking that question.

It’s not like the market wasn’t due for a pullback. One hundred points on the NASDAQ, after a torrid run in 2017, really isn’t big news. But it was the intensity of the selling that was notable. Almost 1.5% percent was carved out (amounting to about four melt-up up days) in two distinct waves of selling. More than anything, it was a reminder of how powerful the downside could be when the world’s biggest one-sided trade tilts in one direction.

But it got us thinking. If a slight miss in jobless claims could cause such conflagration in the market, what happens when the economic data gets really bad? That’s not something investors are thinking about at the moment.

And why would they? The U.S. economy has experienced two consecutive quarters of three percent growth (both business cycle highs). Business confidence is still near 20-year highs and consumer confidence is doing okay. All major stock markets are busting out, and many Americans (wrongly) view the markets as the ultimate benchmark of economic strength.

But the trick is understanding where the economy is going, not where it has been. More importantly in today’s age, it’s knowing where the liquidity will come from to help keep prices elevated. That view is murkier.

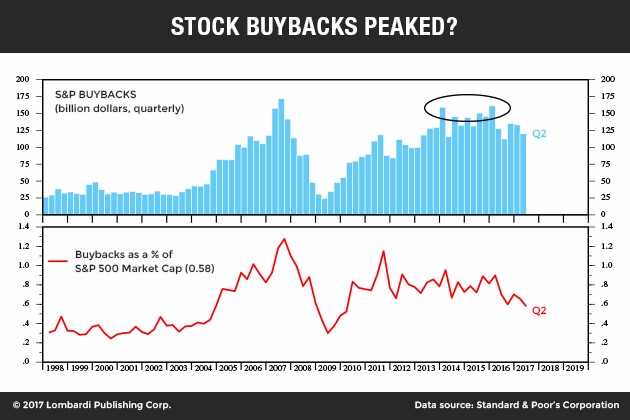

For example, the Federal Reserve is about to engage in a quantitative tightening (QT) program to reduce its balance sheet. The Fed will taper bond purchases and allow bonds on its balance sheet to mature. Bond purchases from their primary dealers have allowed banks to plow the proceeds back into the stock market. When this program ends, where do the next liquidity injections come from?

Some analysts predicted that corporate share buybacks would soar in 2018, on the back of Trump’s tax cut plan. Goldman Sachs Group Inc chief U.S. equity strategist David Kostin predicted that $150.0 billion of that cash would go to buybacks. Bank of America believed that Trump’s tax plan could add as much as three percent to earnings per share (EPS) growth in 2018. (Source: “Buybacks Are a Hard Habit to Break,” Bloomberg Gadfly, May 3, 2017.)

But, with bipartisan support for Trump’s tax plan fading, it is looking more like a dud by the week. I’m sure something will pass, but it might be watered down to the point of irrelevancy; at least, for a corporate tax cut perspective.

The Completely Overlooked Chinese Catalyst

According to some reliable sources, the Chinese debt dyke is about to burst. Chalk this up as a potential black swan event hiding in plain sight.

According to the China Beige Book, a $100,000-per-year detailed research service about Chinese enterprise, China’s epic debt binge is about to unravel. Now that President Xi Jinping has been re-affirmed as leader by the National Congress of the Communist Party of China, it is said that he will tackle the debt problem head-on. (Source: “Warnings From The ‘China Beige Book’,” Zero Hedge, November 12, 2017)

The country is facing a painful re-balancing, as decades of overcapacity and voracious debt issuance is coming to a head. So much so that China’s debt-to-equity ratio is over 300%, which is well over America’s, and is very close to Japan’s, a certified debt basket case. Huge tracts of the economy are akin to Ponzi schemes, and there’s only so many ghost cities that the government can build to prop up the mirage of “strong growth.”

Ultimately, if China does experience economic turmoil from within, the global economy will suffer a recession. China is now the world’s biggest economy; it’s no longer the case that America “catches a cold and the world sneezes.” A Chinese slowdown won’t just hurt bilateral trade; it will have peripheral effects with global trade partners in a domino effect.

When a recession arrives, a market crash will occur, period. Why? There’s zero chance that historically high valuations can be sustained when earnings decline 50% or more, which always occurs during recessions.

My Verdict

Whether it’s a Chinese slowdown or a U.S. recession brought about by old age, staking a large position is fraught with risk. Nobody knows when it will end, but the rewards seem quite restrictive.

The investing climate has never been so difficult, because it has never been driven by such overt central bank action. That activity (and presumably, much of the fuel to keep it going) is set to decline in 2018. Whether this turns into a 2000-like market crash, or something more benign, is anyone’s guess.

Investors best proceed with extreme caution, with put protection in hand. Falling for normalcy bias at the end of an historic rally is a very expensive lesson.