Orchestrating a Market Crash Via Interest Rates Would Solve a Lot of Problems

The Federal Reserve is embarking on an interest rate hiking cycle, but why? By all accounts, the economy is muddling along, and inflation is tepid. The economy isn’t exactly setting the world on fire. So what gives? The reasons matter, because reading the tea leaves correctly could help you position yourself to avoid a market crash.

To understand the Federal Reserve’s hawkish logic, we must recognize what their stated mandate is. And that is, 1) to achieve maximum employment, 2) to foster stable prices, and 3) moderate long-term interest rates. During strong economic periods, points 1) and 2) may become imbalanced, forcing the Fed to raise interest rates and satisfy point 3). Rising interest rates are the anchor to keep wage growth and price demand in check. But that’s not what we’re witnessing today, making the Fed’s insistence on raising rates puzzling.

Also Read:

The Janet Yellen Rate Hike Could Unleash U.S. Financial Collapse 2017

For example, U.S. GDP only grew at 0.7% in Q1 2017, which was lower than the 2.1% growth experienced in Q4 2016. It was also the weakest overall quarter in three years. (Source: “U.S. first-quarter growth weakest in 3 years on low consumer spending, GDP rises 0.7%,” Business News Network, April 28, 2017).

Any suggestion that the Fed is raising rates due to a strong U.S. economy is absurd. Peak economic growth of this business cycle has already passed.

Even the notion of strong labor markets is more economic fake news. The headline unemployment number of around 4.4% looks fantastic (lowest is two decades). However, the devil is in the details. Most of the jobs created are of the low-wage, transitory variety. Stable and moderate-paying manufacturing jobs still haven’t rebounded from the Great Recession. Almost all of the gains have come in the service sector, with some sustained strength in healthcare.

While the latter sector provides stable and respectable paying jobs, the former does not. Besides, there are only so many waiters, maids, and bartenders that businesses need, and these jobs are easily shed if the economy contracts once again. You can look through the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statics (BLS) numbers yourself, or you can just listen to the words of a former economic advisor to Barack Obama, Alan Krueger. In December 2016, Krueger admitted that a whopping 94% of jobs created since the Great Recession were temporary positions. “Workers seeking full-time, steady work have lost,” said Krueger. (Source: “Nearly 95% of all new jobs during Obama era were part-time, or contract,” Investing.com, December 21, 2016).

As for the consumer price index (CPI), the highest yearly gain since 2008 was 3.2%, which occurred in 2011. In the last four years, it hasn’t risen by more than 1.6% year-over-year. This completely debunks the notion that the Fed is raising rates to foster stable prices. They are already stable. If anything, raising rates will further discourage demand and threaten to tilt CPI into negative territory. This would be contrary to the Fed’s two percent inflation mandate. (Source: “Consumer Price Index: Total All Items for the United States,” Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, last accessed July 17, 2017.)

Given that the economy has already peaked, and consumer prices are very stable (almost too stable, if that’s possible), again I ask: “Why is the Fed hell-bent on raising interest rates? Why would they risk hammering the death knell into a still fragile, uninspiring recovery?”

It doesn’t make any sense until you dig deeper into the backstory.

What Is the Fed’s Real Agenda?

The Fed’s determination to hike rates makes even less sense because they are notoriously data-dependent. It’s not even a matter of interpretation; clearly, economic conditions do not warrant such aggressive action. Such peculiar reasoning is getting some very smart people to question the Fed’s true intentions. If their logic is correct, the implications for the stock market are profound.

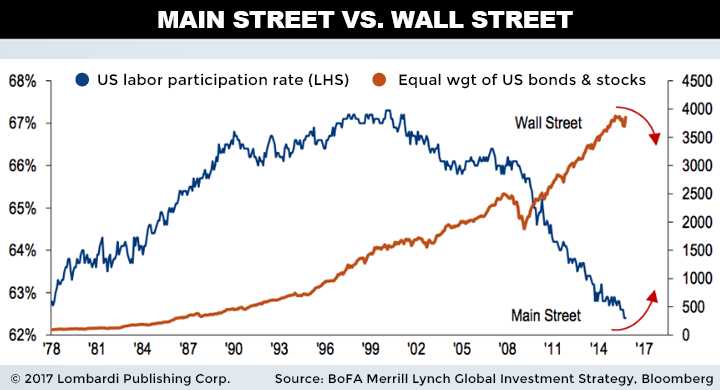

Societe Generale strategist Albert Edwards thinks he knows why. Edwards cites recent hawkish statements from the Business of International Settlements (BIS) regarding instability caused by asset bubbles to conclude that “the Fed has two ways to cure inequality…you can make the poor richer…or you can make the rich poorer…” This piggybacks on a chorus of other analyses that is increasingly questioning the Fed’s motives. Bank of America analyst Michael Hartnett also recently noted that the Fed has become “increasingly concerned about the inequality QE has produced.” (Source: “Albert Edwards: ‘Something Smells Different This Time’,” Zero Hedge, July 6, 2017).

So again, why does this all matter? It matters because, if the Fed is targeting wealth inequality over satisfying their three primary economic mandates (see earlier), a market crash is sure to happen. Why? Because it means the Fed is determined to prick the stock market bubble to avert further problems down the road. Ultra-low rates have accomplished all they could, but it basically only helped the top 20% of society. Since low rates failed to raise living standards of the bottom end of society, the Fed will attempt to tamp down on the top end to bring all classes closer together.

No doubt the Fed understands that this will cause a recession, but one is coming anyway. If the Fed doesn’t raise rates now, they’ll have no ammunition to help stimulate demand later. This would make the coming recession much harder to shake.

Ultimately, if Edwards is correct, the Fed will continue to hike rates until a stock market correction occurs. If promoting asset price inflation (wealth effect) with low interest rates couldn’t get the economy growing rapidly, nothing will. The Fed may now be focused on doing the opposite: reversing the wealth effect to stem off the collateral damage that high asset prices cause during a recession. It’s a departure from the logic that usually governs the Fed, but it makes sense.

Under such conditions, the stock market is not the place to be for the foreseeable future. The Fed may desire a controlled correction, but a market crash might be the ultimate outcome. Inflated asset prices and a recession caused by rising rates do not make good bedfellows.